Historical Review

From the Floating Log to the Palace at Sea - A short summary of 6000 years of navigation

Concerning the question what has been the earliest means of transport Man has developed, there is no doubt about: it was the boat. The African lakes are considered the region where mankind is coming from. However, until now it is not known how Homo Sapiens has reached Australia some 60,000 years ago, across the estimated 60 miles distance from Asia at that time. Long before riding on the back of an animal or using the invention of the cart, Man took advantage of the log floating on the water. He found out how to hollow it out with fire and his primitive tools. Later on, parapets were put on and thus the log became the keel of a boat. The planks were fastened by strings and later by wooden rivets, in other cases some logs were strung together to make a raft of greater stability. Motion was managed by hands, with sticks or diverse forms of paddles until Man discovered how to make usage of the force of the wind. Pictures of Egyptian sailing vessels made of bundles of papyrus reeds have survived from about 4000 years B.C. Around a millennium later, the first wooden ships with sails appeared on the Nile. One of the most fascinating and most lasting adventures of mankind has begun. The sagas of Odysseus and the Argonauts may give us an idea of maritime exploration in the Greek antiquity. Following Homer, Jason crossed the Aegean Sea and passed the Dardanelles for the Black Sea in quest of the Golden Fleece. His ship, the "Argo", had been for a long time preserved on the beach of Colchis as the prototype of the early seagoing galley.

During the era of the Roman Empire, broad-beamed merchant ships brought a large variety of goods from the Nile Valley to Ostia, the port of Rome. Their development was based on the researches by Archimedes and other scientists, who knew also that the earth is a planet revolving around the sun. A vivid report of navigation from that period has been delivered by the Bible with St. Paul's Act of Apostles, when he was sent as prisoner to Rome and suffered shipwreck ashore of Malta. In the northern hemisphere, about 900 A.D., the Vikings were the first to cross the Atlantic out of their Scandinavian fjords to settle on the coast of Newfoundland. In their open but well-constructed Dragon boats, moved by oars or a single sail, they carried merchandise, livestock and all things they needed to live there. An early prototype was found at Oseberg near Oslo in 1904 which has been preserved. It is clinker-built, i.e. the planks overlap downward, being fastened by iron rivets.

A dark chapter in history followed with the four Crusades between 1096 and 1199. The Mediterranean ships of the time were high-boarded with castles fore and aft upon a carvel-built hull (with flush assembled planks). An innovation has been the triangle lateen sail taken over from the Arabs. While the Hansa had been engaged with establishing a mighty trade empire along the shores of the Baltic with outposts as far as Novgorod in Russia, Bergen in Norway and on the French Atlantic coast, a new age of enlightment had led to a changed view about things independent of religious traditions. Researchers like Copernicus, Galilei and Kepler demonstrated that earth is not the center of the universe. Improved nautical instruments helped seamen with navigation and ships with more masts, fitted with rudder on a stern-post instead of the side-oar of the past, enabled to traverse vast areas of sea.

Columbus monument, Barcelona (WS)

|

Columbus' "Santa Maria" (old card, coll. WS)

|

When the Genoese Cristoforo Colombo (in Spanish Cristobal Colon, better known as Christopher Columbus) set sail in search for a shorter, westward route to India in August 1492 on behalf of the Spanish Queen Isabella, he opened the door to a new chapter in history. After nearly 3 months at sea, full of danger and privations, he set foot on land which he took for India but was in fact an island of an unknown continent - America. The country discovered on the first voyage was probably Guanahani, an island of the Bahamas, followed by Cuba and Haiti, the latter then named Hispaniola. Having been convinced of his belief, he took the friendly natives for "Indians". His flagship "Santa Maria" belonged to a new high-boarded, three-mast type of vessel, the Nao. Information about her is very scanty. Her length from bow to stern is supposed having not exceeded 86 ft. (28 m) and she carried castles fore and aft. After having stranded on a sandbank ashore of Haiti, she had to be abandoned. Columbus returned on the "Nina", accompanied by the "Pinta", both of the older caravel type. Columbus' harsh rule over Hispaniola provoked an upheaval even among European settlers and during his third voyage he was arrested and delivered to the Spanish crown as a prisoner. Nevertheless the Queen enabled him to undertake a fourth voyage, he discovered the coast of Central America, but returned after a year as a shipwrecked person. The new King Ferdinand showed little interest in the great discoveries and Columbus died in 1506.

Voyages of other discoverers followed in short intervals. In 1497/98, the Portuguese Vasco da Gama sailed round the Cape of Africa and got onto the direct seaway to India. On mission of the British Crown, the Anglicized Italian John Cabot discovered about 600 years after the Vikings for a second time Newfoundland and entered from there into the St. Lawrence Bay in 1498, but failed the northern route to China (Cathay) he was in search for. Another Italian, Amerigo Vespucci, sailed down the coast of South America as far as the La Plata in 1499. The new-discovered double continent was later named after him. An unsurpassed endeavour was the first circumnavigation of the globe by the Portuguese Fernao de Magalhaes (generally known under the name Ferdinand Magellan) between 1519 and 1522, in Spanish service. Out of his little squadron of 5 ships, carrying crews of 265, only the flagship "Victoria" returned with 18 survivors in desolate state. Magellan was killed during a fight between hostile tribes on the Philippines. The second to follow him was the English corsair Francis Drake in 1577/1578. His well-appointed expedition, entrusted by Queen Elizabeth I, was a mixture of exploration and piracy. He plundered treasure galleons of the Spaniards and looted towns in their American colonies. To their great annoyance, the Queen who had shared in his ventures awarded him with the knighthood. The age of Discovery signified the end of the Medieval Ages and opened the door to a more liberal thinking. On the other hand, it was followed by an invasion of 'conquestatores', missionaries and slave-traders heading for the colonies. Over the centuries to follow, the sailing ship had not only gained in size and technical perfection, but has also become one of the most beautiful creations of art, equipped with elaborate decorations, carvings and artful galleon figures from the 16th to the 18th century. The East India Companies of the British, the French and the Dutch owned fleets of well-found merchant ships which belonged to the finest ever. For keeping corsairs away the Indiamen were well-armed. Occasionally it had turned out that painted gun-ports along the hull did the same.

Replica of the Portuguese "Flor de la Mar", Malacca (WS)

|

"Bounty" replica, Sydney (WS)

|

Representative for the 18th and the early 19th century, two noteworthy barks should be mentioned in particular: "H.M.S. Endeavour" and "H.M.S. Beagle". The former, a converted collier, served Captain James Cook to circumnavigate the globe from 1768 to 1770 when he was out for the observation of the transit of the Venus through the sun and to explore New Zealand and Australia's east coast. The other vessel, the "Beagle", carried Charles Darwin to South America and via the Magellan Straits to the Galapagos Islands and to Australia between 1825 and 1841. As a result of his studies he developed the theory of the origin of species. Although both vessels had been equipped on mission of the Admiralty, they were no fighting ships, intended only for scientific exploration and not to take possession of new soil for the Crown. Its last and most splendid climax reached the sailing ship in the form of the high-towered clipper with six storeys of square sails becoming the real queen of the oceans. The Golden Age of the clipper ships was actually being related to the fabulous Gold Rush in California of 1849, when thousands of diggers with their supplies and tools took the seaway round the treacherous Cape Horn heading for San Francisco since the absence of rail or road connection through the Rocky Mountains. Names like those of "Flying Cloud", "Lightning", "Sovereign of the Seas" or "Great Republic", to mention only a few of the most prominent ones, designed by Scottish-born Donald McKay of Boston, may stand for their pattern. On June 2nd, 1851, the "Flying Cloud" has set a record when she covered the passage of about 10.800 miles (20.000 km) in 89 days and 21 hours that never has been surpassed by a ship under sails. Those had been the days of wooden ships and iron men.

"Das Wappen von Hamburg" of Hansa, near Helgoland (painting by Heribert Schroepfer)

|

"Thermopylae" (in front) and "Teaping", tea race Kowloon - London (painting by Heribert Schroepfer)

|

A clipper and the first "Kaiser Wilhelm II" (painting by Heribert Schroepfer)

|

"Potosi" of Laeisz, 1905 (painting by Heribert Schroepfer)

|

"Polly Woodside", an American Cape Horn vessel, Melbourne (WS)

"Polly Woodside", an American Cape Horn vessel, Melbourne (WS)

Before we turn towards the Technical Age, let us have a look at the nautical state of affairs in other areas of the world. In generally, our knowledge of the Far East has remained rather scanty. What sorts of vessels were used when people from New Guinea discovered South Pacific islands between 2000 and 1500 B.C.? Around 700 A.D. people from Borneo have settled Madagascar, but the way is unknown. The earliest reports we owe to the Venetian Marco Polo, who was the first European to travel in the 13th century to China and South Asia, though overland. He reported a variety of seagoing Junks. Their characteristic features, flat keel-less hull, raised stern and two to five masts carrying lug-sails (the bigger one ahead) remained little changed until our days. Junks provided the entire coast and river trade. Reports of even nine-mast Junks having brought rare merchandise and spices from the Orient as far as Arabia and East Africa in the 14th and 15th century have been delivered. The Chinese Junk has been taken over as prototype by the Japanese.

Schematic of a Dhow with 3 masts (KVDP, via Wikimedia)

|

Chinese Junks, c.1850, attributed to George Chinnery (via Wikimedia)

|

Dhow is the collective term used to denote a number of different Arab vessels, sailing for centuries mostly out of the Persian Gulf ports making voyages down the East Coast of Africa, into the Red Sea and to India. Usually they carried two lateen sails. Dhows have also been used by slave traders.

Of similar design has remained nearly unchanged up to the present over centuries the Malayan and the Indonesian Prow. Seagoing vessels of New Guinea and the Pacific Islands have been typical for their double-hull (catamaran), joint together by beams which support a bamboo deck with a cabin upon. Each hull was carrying a light bamboo mast with a high sail bent to elastic spars. Single-hull vessels were stabilized by out-riggers. Other patterns of seagoing craft have remained of less importance.

Early in the 19th century a new kind of propulsion has come into existence: the steam engine. After various experiments which can be followed back to the late 1700s, it has been James Watt who improved the invention until economic application. The first vessel using steam power was in 1802 the little "Charlotte Dundas", intended to tow barges instead by horses on the Forth of Clyde Canal in Scotland, though only temporarily. The first who has built a steam boat that operated successfully on the Hudson River between New York and Albany was the American Robert Fulton with his side-paddle wheeler "Clermont" in 1807. Five years later, the little "Comet" (21.5 tons) took up regular passenger service in Great Britain between Glasgow and Grennock. Lasting fame gathered eventually in 1819 the American sailing ship "Savannah" for the first crossing of the Atlantic by using her auxiliary steam engine for some time. But it took another 18 years to make steam power the main propulsion. The smaller steamship "Sirius" of only 703 tons entered unexpectedly the pages of maritime history as being the first to arrive in the New World having crossed the Atlantic under continuous steam power in 18 days and 10 hours, when she had to help out for another ship that had suffered from fire. Only slightly later the much bigger "Great Western" (1,320 tons), designed by the ingenious Isambard K. Brunel, cast anchor in New York Harbour. Thereafter she took up her first regular transatlantic passenger service between Bristol and Boston, taking about 15 days for a passage. She was luxuriously appointed and proved being outstandingly successful, at last in the Indian trade. Gradually the steamship began to replace the sail from the ocean and navigation became widely independent of wind and weather.

The one-cylinder engine of the "Savannah" produced 90 h.p., enabling her to make a transatlantic passage in 29 days. The "Great Western", fitted with a two-cylinder side-level engine receiving steam from 4 boilers giving her an output of 750 h.p., cut the time to 15 days. The next step was the four-cylinder balance-level engine in combination with improved paddle wheels which were steadily kept in vertical position to minimize the counter-pressure when plunging into the water. A new flue-tube boiler replaced the inadequate box-type which was later relieved by the more effective waterflue type that allowed to raise the working pressure substantially. However, efficiency and fuel consumption remained yet unsatisfactory. A great advance towards thermal efficiency was achieved by the adoption of the multiple cylinder compound engine expanding the steam in two, three or even four stages. Additional energy savings were gained by superheating of the steam through an arrangement of tube-bundles. The final standard in steam power technology was attained with the high-pressure turbine in combination with oil-firing that has been maintained until the present.

It was self evident that also the drive had to be undergone some improvements. The paddle wheels, having proved being rather vulnerable at rough sea, gave reason to experiments with several forms of screw drives. The Austrian Joseph Ressel was the first in the field, having invented it in 1827, but missed to apply for a patent. Also the Swedish John Ericsson is credited with having created the screw drive. The Englishman Francis Smith took the fame for the practical application. When in 1845 the attractive, six-mast "Great Britain" set out on her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York, she was the first screw-propelled ocean ship on the Atlantic and with a gross tonnage of 3,279 the greatest vessel afloat. Her strong iron hull with watertight compartments prevented her loss after a grounding on the rocks of Ireland, thus proving again Brunel's ability in maritime engineering.

Shipping companies however were not yet fully convinced of the new form of drive. Therefore the British Admiralty supported a test between a screw- and a paddle -driven steamship of equal size and engine power, "Rattler" and "Alecto". Towed together stern by stern, the screw-propelled "Rattler" pulled away her opponent easily... When shipbuilding changed from wood to iron and later to steel the ships grew to tremendous size. The ocean liner was no longer a mere link between continents but had rather become a symbol of national pride. To win the "Blue Riband" - a fictive award for the fastest Atlantic crossing - has been made the great target of leading navigation companies.

I.K. Brunel's success with the "Great Western" and the "Great Britain", each the largest ship of the time and milestones of progress, encouraged him to construct a third one, the dimensions of which should surpass those of the "Great Britain" by six-times the size. The result, an immense iron ship of 18,915 tons at a displacement of no less than 27,859 tons and 680 ft. (211 m) length, the famous "Great Eastern", launched in 1858, remained unsurpassed for the next 40 years. A double-walled hull with 12 watertight compartments should care for a high standard of safety. With her five funnels, 6 masts with auxiliary rigging, both paddle wheel and screw propulsion providing an output of 4,200 h.p., she made a strong impression on her contemporaries. On trial she attained a maximum speed of 14 knots. However, what was supposed to become one of the wonders of the century turned out as a giant of misfortune. It started with a failed launching causing a delay of a quarter of a year, followed by a boiler explosion with 6 casualties, a drowned captain, nearly getting shipwrecked in a storm and being occupied only by a fraction of the passengers hoped for, her way was paved into bankruptcy. Brunel grew sick and died from these worries. His decision for such a giant ship arose not out of a sheer megalomania. Due to her name, the "Great Eastern" was intended to carry 4,000 passengers to India and Australia without having to call on ports for re-coaling because. That meant the provision of an immense bunker capacity. Instead however the ship took up service on the customary Atlantic route. Having never come up to the expectations, she was converted and was for a time successful in laying telegraph cables across the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean. Far ahead of her time, she proved a commercial failure giving the lesson that dimensions must grow organically step by step when demand is being called for. Used as an exposition ship for a time, the "Great Eastern" was sold for scrapping in 1888, still unexceeded in size.

One of the greatest events of the 19th century was the opening of the Suez Canal on November 17th, 1869. On order of a French association, Ferdinand de Lesseps executed the plan of Italian-Austrian Alois Negrelli for the 160 km seaway through the isthmus between the Mediteranean and the Red Sea which shortened the connection to India by 7,125 km (3,780 miles), cutting the traveling time by about one month. The ceremony was crowned with a procession of 65 steamships, conducted by the imperial yacht "L' Aigle", having on board Empress Eugenie of France. In memory of the day Giuseppe Verdi composed one of his most successful operas, "Aida". Because of the restricted width, the Canal was not suited for sailing ships what signified the approaching end of the clipper gild.

Alone in great Britain the number of sailing ships fell between 1888 and 1908 from 15,111 to 9,520 while that of the steamers increased from 6,638 to 11,361. By the introduction of the multiple compound engine and other advances in marine engineering the fuel consumption could be cut by half. Twin triple and quadruple screw propulsion helped to gain on speed substantially. And what has become most important: The independence of wind and weather has enabled the steamship to operate on regular schedules. Yet the supporters of the canvas would not give up the fight. With a last effort the promoters of the wind power pointed out its advantages against the steam. Until the outbreak of the First World War the tallest sailing ships ever built crossed the oceans. Especially German owners like Ferdinand Laeisz and R.C. Rickmers boasted their four- and five-mast full- or bark-rigged vessels, some of Rickmers' equipped with auxiliary engine, tried to withstand the competition. But neither these superbly finished "Windjammers" of the post-clipper era were able to stop their eclipse. This review however should not be concluded without commemorating three of the most outstanding representatives of the species. The tallest sailing ship ever built has been the "France" (II), introduced 1913 by the Societe Anonyme des Navires Mixtes on New Caledonia services via Cape Horn. Rigged as a five-mast bark of 5,806 tons (five-times the size of a clipper), with a length of 126 m, she was towering up to the height of a 15-storeyed house. Accommodations for 25 first-class passengers were provided. On a voyage to New Caledonia in 1922 she was carried by a strong sea current on a coral reef and had to be abandoned. Another vessel worth to be mentioned here was the American schooner "Thomas W. Lawson", built in 1902, having been unique being the sole 7-masted ship in the world. In spite of her length of 123 m and a tonnage of 5,218 she could do with a crew of only 16. Yet after a lifetime of only five years she suffered shipwreck at the Scilly Islands. No less fame goes to the greatest and sole full-rigged five-mast ship ever afloat: The German "Preussen" of the famous Laeisz Family. Unlike the "France", the "Preussen" depended only on her 5,600 sqmts. of canvas and was never equipped with an auxiliary engine except for the winches to serve the sails. Measuring 5,081 tons and with a length of 133 m she has been the last word in sailing ship construction. Her operating field was to be the West Coast of South America. On November 6, 1910 at midnight, she was rammed by the Channel steamer "Brighton" near Dover, then drifted steerless on a cliff and was wrecked in storm. All these three outstanding vessels had in common an all-steel construction, a loading capacity of about 8.000 tons - and shared the destiny of a fatal end. None the less, the last of the gild succeeded to survive even the opening of the Panama Canal, two World Wars and the economic crisis between and after.

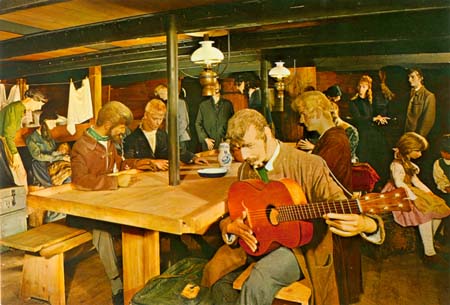

Replica of a steerage deck for emigrants (Deutsches Museum, Munich)

Replica of a steerage deck for emigrants (Deutsches Museum, Munich)

Growing traffic demand by merchantmen and, not to forget, the rising emigrant traffic, necessitated a continuous development in shipbuilding and technology. During the last decades of the 19th century the triple expansion engine topped a height of no less than a 6-storeyed house and its some 28,000 h.p. enabled to a speed of about 22 knots. It seemed having got to its utmost limits. When running at "full ahead" the vibrations became nearly unbearable, so that even on some occasions propellers got lost. Liners of that characteristic were soon nicknamed "cocktail-shakers". Just in time, three technical achievements contributed to a last perfection of the ocean liner: The steam turbine, the oil-firing and - alternatively - the diesel engine. Not only they helped to ease the hard work of firemen and machinists essentially but brought also about a soft running. When in 1912 the first ocean-going motor ship, the Danish "Selandia" of the East Asiatic Co., went on her maiden voyage to Bangkok, it was the start of a revolution in shipbuilding. It took yet another half a century to convince the shipping companies of the superiority of the inner-combustion drive: Less personnel, no smoke, no ashes and on the other hand high efficiency and increased utility of the tonnage. Today the world's merchandise fleet, cruise ships included, is diesel-powered. In 1954 the first nuclear-powered submarine of the U.S. Navy, the "Nautilus", came into service. Nuclear power entered commercial shipping for the first time in 1959 with the Soviet icebreaker "Lenin". In 1964 the "Savannah", built in 1961 as the first passenger-cargo steamship using nuclear energy, was introduced on USA - Mediterranean cargo services. In 1972 she was laid up to become a museum.

German pride of the steam age: The "Europa", entering the mouth of the Weser (painting by Heribert Schroepfer)

French pride of the steam age: 'Le grand salon' aboard the "Normandie" (Deutsches Museum Munich)

After World War II, most of the old shipping companies and some new ones took up the former services and a lot of new passenger tonnage was launched hoping that extravagant facilities and splendour would take sufficient care to get the cabins occupied. But when in the late 1950s the new generation of jetliners cut the flying time between the Old and the New World to less than 8 hours, more and more travelers put up with the cramped conditions of the rivals in the air. Within less than one decade the ocean liner has lost most of its clientele. Floating palaces like the classic British "Queens", the beautiful "France", the elegant "Michelangelo" or the speedy "United States", once symbols of national pride and potency, lost much of their prestige and became relics of yesterday nearly overnight. It was the end of an era.

But this was not the end of the passenger ship. The phenomenon of road traffic created a fast-growing car ferry operation connecting not only islands with the mainland, but even countries. With regard of size, speed and comfort, some 'cruise ferries' have come close to the glorified ocean liners of the past. A separate chapter is devoted to the development of the branch lines of the bygone epoch to nowadays' ferries.

"Europa Palace" and "Olympic Champion", racing across the Adratic Sea (WS)

|

Lounge aboard the "Olympic Champion" of ANEK (WS)

|

The disappearance of the ocean liners did not mean the end of prestigious shipping at all. Rather it gained importance in another field of activity in the form of the cruise ship. The first ones have been converted ocean liners, but they were soon followed by ships appropriately designed to suit the new purpose. The new clientele was now expected to feel being on holidays and not on business trip, the voyage was to become the target itself and speed an unimportant factor. Hand in hand with the expansion of the facilities, the cruise ships were getting larger and larger, meanwhile having dwarfed even the biggest ocean liners of the past. At a tonnage of much more than 100,000, they dispose upon accommodations for thousands of holiday guests heading for the loveliest shores and cultural sites round the world.

"Mariner of the Seas" of Royal Caribbean, Jamaica 2008 (WS)

|

"Mariner of the Seas", the Royal Promenade (WS)

|

"Celebrity Equinox", Piraeus 2009 (WS)

"Brilliance of the Seas", Santorini 2007 (WS)

Download this picture with 1500 pix, 300 dpi

|